I have been reading quite a bit on Baloch musical traditions for the past week and well, there is a lot to cover. But you, dear reader, are probably wondering about the title. Well, I’m not kidding around. So, let’s dive right in. I came across this story through this article by Ajam Media Collective.

Sufi Hispano-Pakistani — Aziz Balouch’s Spanish Odyssey

Let’s begin by taking a trip to the Gibraltar in the 20th century. After the establishment of the Suez Canal, trade everywhere exploded. The Indian Subcontinent was now directly connected with Europe and traders and merchants from all across took advantage. Our story begins with one Aziz Balouch. Born Azizullah Khan Al-Zahidi in 1910 in Balochistan, Aziz Balouch was a Sufi devotee turned musician. After the death of his father, he left Balochistan for Pir Pagaro’s dargah and his formal education began with the poetic traditions of Sufi saints.

Aziz Balouch in 1934

When he was of age, he left the dargah for the city of Hyderabad where he found work and his new passion: flamenco, introduced to him by a Hindu friend. The same riend who had introduced Aziz to this music was a merchant often travelling to Gibraltar for business and so, he offered Aziz a job opportunity there. Both the fascination for this music and Aziz’s own interactions with the Sufi traditions then took him to Al-Andalus. In his memoir, he described his first glimpse of the Iberian Peninsula, “when I beheld the Rock and the Castle of Tariq, the frontiers and the first vistas of Southern Spain, I felt like one returning to his own land.”

Despite working in Gibraltar for a year, Aziz had still not met flamenco yet, until he moved to Madrid. This is where his odyssey would truly come to fruition.

Aziz Balouch and a group of people who bid farewell to bullfighter Domingo Ortega on the occasion of his departure for America, La Voz de Madrid on November 19, 1931.

In 1932, he would perform in the town of La Línea with flamenco greats Pepe Marchena and La Niña de los Peines. Aziz performed a rendition of La Rosa and was so impressive that the flamenco community nicknamed him ‘Marchenita’ (little Marchena). His Madrid debut was memorialized in this poster (digitized by Stefan Williamson Fa).

‘The Indian who sings flamenco, a disciple of Marchena with his magical instrument’

Aziz believed all of his loves were connected. In A Cartographic Exercise, Elridge quotes that Aziz Balouch “hears” a connection between his own twelth-century Sindhi Sufi music and twentieth century Flamenco. I couldn’t tell you what exactly he felt or even provide an academic basis for why a Baloch whose identity was shaped by Sindhi Sufi traditions, felt this particular connection to flamenco. He actively seems to breakdown our conceptions of homogenous territorial space and what it means to belong to a culture, or really what culture, where?

According to González, the connections Aziz made between flamenco, 8th century Andalusia, and Sindhi Sufi traditions were far from superficial. He believed that the 8th century singer from Caliph Harun Al-Rashid’s court Abu al-Hasan Ali ibn Nafi better known as Ziryab (blackbird) inspired the flamenco tradition. Interestingly, his own mentor Pepe Marchena even said that he considered him to be “a second incarnation of Ziryab, the one who came eight centuries ago to teach music to the Andalusia of that time.”

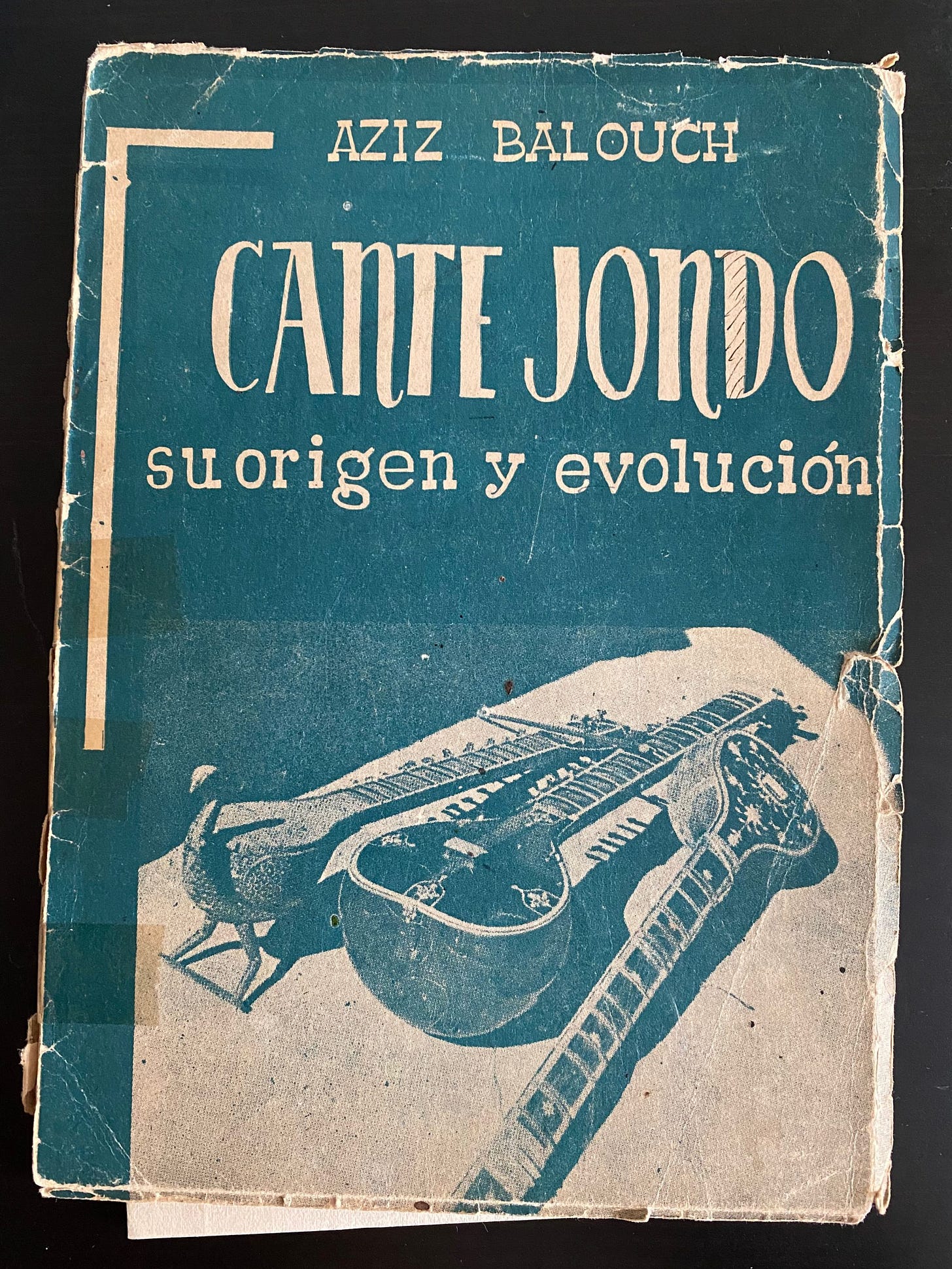

Aziz also believed that flamenco, Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai’s Risalo, and the Haidari traditions of Sindh surrounding the mourning of Imam Hussain were all tied together with the same thread. It makes sense as well, considering flamenco is known to be ‘sung from pain’. He detailed these connections in his publication Cante Jondo: Its Origin and Evolution (1955).

Aziz wrote

Just as in Spain, the songs in the Holy Week are sung in processions

without instrumental accompaniment except the drum, so are

the marsiya in Sindh as well as in other parts of Pakistan sung only

to the accompaniment of a drum. The most typical of these songs,

falling within the general category of the marsiyas sung exclusively

in the Lower Indus Valley of Sindh, are known as Osara. The

semblance between the Osara of Sindh and the Saeta religious

songs of Cante Jondo is typical.

He drew connections between the music itself as well, relating them through common themes such as romantic lyrics, religious poems and sorrowful longing being fundamental to a lot of the tradition.

Just as the Spanish Seguidilla and Soleares are expressive of sad concerns (separation, longing, or even deep sense of fatalism), so are the Sindhian Desi, Kohiyari, Rano, Lorraoo.

Just as his mentor thought him as an incarnation of Ziryab, Aziz believed flamenco to be an incarnation of his beloved Sindhi Sufi music.

In 1962, Aziz Balouch recorded his one and only catalogued record named, ‘Sufi-Hispano-Pakistani’, taking his love for flamenco and sufi poetry in Sindhi, Arabic, and Persian to create a masterpiece. This is from one of the tracks translated and quoted by Williamson combining the poetry of 12th century poet Sanai with the Spanish seguiriya.

ملکا ذکر تو گویم که تو پاکی و خدایی

نروم جز به همان ره که توام راه نمایی

Oh King, I sing your praise, for you are pure and regal

I shall not fare except on the path that you have pointed out to me

Ahora tú vienes hincá de rodillas pidiendo perdón,

te apartaste de mi vera y te fuiste sin apelación.

Now you come to me on your knees begging forgiveness,

You left my side ignoring my appeals.

Here is the full album:

The serious article ends here, but if you want to read a bit of my nerding out and grasping for straws, do continue.

A shakier connection

While reading George Mürer’s very interesting article titled ‘The Forging of Musical Festivity in Baloch Muscat: From Arabian Sea Empire to Gulf Transurbanism to the Pan-Tropical Imaginary’ (rather wordy), I came across an interesting iteration of Balochi musical tradition in Oman. While discussing contemporary music evolutions, Mürer highlighted a group knows as the Los Balochos, an informal Gypsy Kings cover band heavily inspired by Latin American and Catalan musical conventions.

Here’s one of the very few clips of a Los Balochos performance that exists out there:

The group disbanded quite a while ago, but to our great luck, a disciple/fan has been uploading some of their hits on both Youtube and Instagram for the past year or so. Their music which consisted of a cacophony of groovy tambourines, guitars, clappers, and a cajòn, led by many singers was mainly renditions of the Gypsy Kings discography. But I found it hard to believe that Los Balochos did not sing in Balochi. Someday, I hope I can find a recording of a full performance. Anyway, to me the music is very much in essence Baloch. Just like Aziz Balouch believed Ziryab was Sindhi and so was flamenco.

We’ll start with this very shaky clip.

The rumba flamenco that was a Gypsy Kings signature can be heard very obviously, each flick and slap on the guitar integral to the rhythm of the song. Now listen to Ustad Amanullah play his Damboora with the same versatility and improvisation. Its fundamentally this ability to not limit the instrument but use it to its full potential, letting that use be a performance really.

Sure it’s a stretch, but I like my joys. Since the group has disbanded their music is being carried on by their disciples who have made sure that the Baloch essence is intact. According to Mürer one of these disciple groups known as the Los Mejores created a medley combining the Catalan Rumba with Reshma’s composition of Dama Dam Mast Qalandar, only to end it with Baloch revolutionary songs. Unfortunately, I have been unable to find that particular recording and I am very jealous that George Mürer witnessed it live.

Here’s a video of the group vibing out that I couldn’t embed directly.

If you kept reading until here, please know that I have much love in my heart for you.

obsessed!